USA v. Google LLC Court Filing, retrieved on January 24, 2023 is part of HackerNoon’s Legal PDF Series. You can jump to any part in this filing here. This is part 20 of 44.

IV. GOOGLE’S SCHEME TO DOMINATE THE AD TECH STACK

C. Google Buys and Kills a Burgeoning Competitor and Then Tightens the Screws

2. Google Doubles Down on Preventing Rival Publisher Ad Servers from Accessing AdX and Google Ads’ Demand

154. After acquiring and killing AdMeld’s innovative technology in order to prevent publishers from having the opportunity to experience real-time competition between Google and rival ad exchanges and publisher ad servers, Google clamped down on similar attempts by publishers to allow Google’s ad exchange to integrate with rival publisher ad servers.

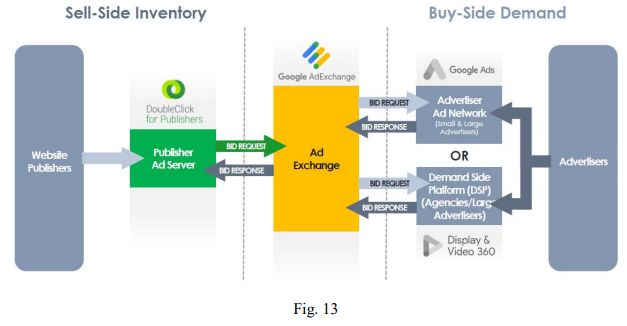

155. By 2015, Google’s publisher ad server, DFP, had reached a 90% market share and had snuffed out most meaningful competition. In part because of the scale that Google’s publisher ad server had achieved by excluding competitors, Google’s ad exchange was large and growing quickly; Google Ads likewise remained the dominant advertiser ad network and an especially valuable source of advertising demand for many publishers. Emboldened by its success, in 2014 Google changed the AdX terms of service to further entrench its market power. Those changes prohibited publishers from using non-Google ad servers, or the remaining yield management solutions, to compare bids from Google’s ad exchange with bids from other ad exchanges in real time, notwithstanding the increased access to inventory such an integration could provide to advertisers buying on AdX. In effect, Google decreed that any publisher that wanted real-time competition involving AdX would have to use Google’s publisher ad server, DFP, formally cementing in policy what Google had intended from the outset of its relaunch of AdX in 2009.

156. Google’s decision was bad for publishers, locking them into a less innovative publisher ad server with artificial limitations on real-time price competition for advertising inventory. It was also bad for any would-be publisher ad server rivals—effectively sounding the death knell for future publisher ad server competition. Google’s exclusionary policy effectively prohibited a competing publisher ad server from offering any form of real-time competition that included Google’s ad exchange and the unique advertiser demand that came with it. Forgoing such competition was a non-starter for nearly all publishers. This restriction is still in place today, an insurmountable obstacle for any nascent publisher ad server competitor.

157. Google built a wall around its exclusive link between its publisher ad server and ad exchange because it feared competition. In particular, Google feared a rival could offer a more attractive publisher ad server by simply allowing all advertiser demand to compete in real time on a level playing field for publisher inventory. More demand competing in real time for publisher inventory generally increases the likelihood that the advertiser that is willing to pay the most for an impression will have a chance to buy it. Rivals that offered technology upending this policy would be seen as offering a better publisher ad server. As one Google employee wrote, if another publisher ad server could place Google’s ad exchange in real-time competition with other ad exchanges, that ad server could offer publishers a “super set of demand” and “[n]o one would sign up for AdX directly” through Google’s publisher ad server.

158. Even though both publishers and advertisers benefit from real-time competition between AdX and other ad exchanges, by policy, Google limited real-time competition from rival ad exchanges to maintain its dominant positions at both ends of the ad tech stack and to further insulate its growing position in the ad exchange market. Google’s decision was based on business, not technology. As the lead architect of AdX explained in an internal email about the policy, “Our goal should be all or nothing – use AdX as your SSP [ad exchange] or don’t get access to our demand.” Indeed, Google had already worked quietly to develop the technology that might allow AdX to integrate in real time with non-Google publisher ad servers. But Google made a “strategic decision” to prohibit such integrations via contract; it terminated its internal projects and blocked efforts by rivals and publisher customers to implement such integrations. That prohibition endures today, and both publishers and advertisers are paying the price for Google’s anticompetitive refusal to innovate or integrate.

159. Now, the only way a publisher can access Google’s ad exchange outside Google’s publisher ad server is by placing an “AdX Direct” tag on the publisher’s website. Even though these tags could benefit buyers on Google’s ad exchange by providing access to additional publisher inventory, Google designed the tags to discourage publishers from using them. They offer only the most rudimentary functionality: publishers can send a request to Google’s ad exchange with a price floor, and if there is an advertiser on AdX willing to pay that price or higher, Google’s ad exchange wins the inventory. No other competing bids are considered, and Google’s bid cannot be compared to other ad exchanges’ bids.

160. Recognizing that AdX Direct is an antiquated relic in comparison to real-time bidding, Google even planned to eliminate the tag entirely in 2019. Google later paused that project as antitrust enforcers focused their gaze on the company’s digital advertising business. But Google has not retained AdX Direct because it is a competitive product offering valued by publishers. Rather, in the words of a Google employee, it merely serves as “a concept for antitrust”—something Google’s antitrust lawyers could claim offers rival ad servers some remote chance of competing on the merits with Google’s ad server. Google’s internal analyses of AdX Direct, however, reflect publishers’ reality: Google’s restrictions make impossible any reasonable substitute for the real-time integration with Google’s ad exchange available exclusively through Google’s ad server.

Continue Reading Here.

About HackerNoon Legal PDF Series: We bring you the most important technical and insightful public domain court case filings.

This court case 1:23-cv-00108 retrieved on September 8, 2023, from justice.gov is part of the public domain. The court-created documents are works of the federal government, and under copyright law, are automatically placed in the public domain and may be shared without legal restriction.