United States of America v. Google LLC., Court Filing, retrieved on April 30, 2024, is part of HackerNoon’s Legal PDF Series. You can jump to any part of this filing here. This part is 18 of 37.

C. Google Has Monopoly Power In The U.S. Text Ads Market

1. Google Has High And Durable Market Share In The Text Ads Market

602. In 2020, Google’s Text Ads market share was 88%. Tr. 4777:21–4778:15 (Whinston (Pls. Expert)) (explaining UPXD102 at 62).

603. Google’s Text Ads market share has been durable; between 2016 and 2020, Google’s share continually exceeded 80%. Tr. 4777:21–4778:15 (Whinston (Pls. Expert)) (explaining UPXD102 at 62).

604. The majority of Google’s revenue comes from Search Ads, supra ¶ 578, and the vast majority of Search Ads revenue comes from the sale of Text Ads. Tr. 1180:25–1181:6, 1181:11–13 (Dischler (Google)) (80% of Search Ads sold by Google were Text Ads); id. 1476:25–1477:5 (majority of Google’s revenue comes from Text Ads); Tr. 4133:3–9 (Juda (Google)) (Text Ads “large majority” of Google Search Ad revenue) (referencing redacted figures in UPX0467 at -331).

2. Text Ads On Google Are A “Must Have” For All Companies Because They Cannot Reach The Same Scale Of Queries Elsewhere

605. As with Search Ads, Text Ads are critical to many advertisers’ businesses; when purchasing Text Ads, however, advertisers have few alternatives to Google. The reasons provided for Search Ads, supra ¶¶ 586–588 (§ V.B.3), apply equally to Text Ads.

606. Because rival search engines’ query volume is much smaller than Google’s, many advertisers cannot shift their Text Ad spend away from Google without significantly reducing the number of impressions and clicks their ads receive; accordingly, shifting is not an option. Tr. 3834:8–3834:11, 3834:22–3835:1 (Lowcock (IPG)) (“The primary purpose of advertising is to reach audiences and to reach people at scale . . . and “scale” means large audience sizes. And so the more scale a search engine has the more important it is to buy advertising on that platform. . . [B]ased on market share, there’s a limit to the amount of keywords we could buy on Bing”) (discussing UPX0450 at .016); UPX0450 at .016 (showing search engine U.S. market shares for Google and Bing at nearly 90% and below 10%, respectively ); Tr. 4875:18–4876:4 (Lim (JPMorgan)) (“Our spend with Bing maxes out where their volume ends regarding the keyword search volume against the terms that we care about as a firm. So once we max out there, which is roughly 10 percent of our paid search budget, there’s no where else to go.”); Tr. 6564:22– 6565:19 (Hurst (Expedia)) (If Expedia stopped advertising on Google, “[t]he only real comparable for the text ads would be Bing, and [Expedia] wouldn’t be able to redeploy all that money in a similar intent environment.”); Tr. 5281:21–5282:12, 5284:6–8 (Dijk (Booking.com)) (Booking.com “would gladly spend more far more” on Text Ads on Bing, but is “constrained because the demand is clearly not there.”).

607. This lack of available alternatives prevents advertisers from shifting away from Google even in response to dissatisfaction with Google’s quality. Tr. 4869:1–4870:11 (Lim (JPMorgan)) (JPMorgan did not shift spend away from Google in response to degrading quality of Google reporting because “Google represents the vast majority of the keyword search interest, the volume in the marketplace. . . Bing doesn’t have an equivalent volume so we would be unable to move budgets between those two partners”); Tr. 5222:20–5223:9 (Booth (The Home Depot)) (The Home Depot did not shift spend away from Google when Google reduced information provided in performance reports.); Tr. 5495:8–16 (Jerath (Pls. Expert)) (Advertisers continue to spend money on Google because “the search traffic is there, they need to tap into it, so Google it is”); Infra ¶¶ 609–626 (§ V.C.4); 1169–1192 (§ VIII.D.2) (describing ad quality reductions).

3. Barriers To Entry In Text Ads Are High

608. Barriers to entry in the Text Ads market are the same as those in the Search Ads market, which are described above. Supra ¶¶ 580–584 (§ V.B.2).

4. Google Has Steadily Made Changes Increasing CPC And Lowering Quality

a) Google Has Increased Participants In Auctions And Increased CPCs

609. As discussed previously, supra ¶¶ 461–465, Google targets its Text Ads by matching advertiser-selected keywords to queries. Advertisers also select “match types,” which dictate how closely the keyword needs to match the users’ query; using match types, the advertiser can expand or narrow the queries for which an ad can appear. Supra ¶¶ 464–465.

610. Over time, Google has limited advertiser control over the specificity of matching, thereby limiting advertisers’ ability to control which auctions they enter and the SERPs on which their ads appear. Tr. 5479:4–5480:17 (Jerath (Pls. Expert)) (providing examples of Google’s expansions to Exact Match and Phrase Match); DX0161 at -542–43 (“Semantic Exact” launch “follows the same spirit as other coverage-increasing” keyword launches.). This affects not just the advertisers unwillingly pulled into auctions they prefer to avoid, but also the other participants in those auctions who see increased auction pressure and, therefore, higher CPCs. UPX1117 at -107 (“[I]ncreased auction pressure” leads to “dramatic” CPC increase under semantic matching.).

611. Advertisers have opposed these changes. UPX0050 at -070 (“Last year, we received criticism in response to Semantic Exact changes. We expect the rollout will result in similar negative sentiment since advertisers and agencies do not see the benefit of this change.”); UPX0921 at -067 (“Although the small changes that Google makes to these types of settings every so often may not seem so significant, they are slowly taking away advertiser’s responsibilities and control. Google’s heavy push on automation through machine learning gives Google the upper hand and ultimate control on what is being displayed on Google Ads.”). Google’s ability to enact these changes, against the will of and to the detriment of advertisers, is evidence of its monopoly power.

612. Google has also eliminated advertisers’ ability to opt-out of those keyword expansions. Tr. 1478:12–14 (Dischler (Google)).

613. For example, Google’s most granular match type is “Exact Match.” UPX8023 at .002. Supra ¶ 465. Exact Match once operated as its name suggests—for ads to trigger, queries needed to contain keywords exactly matching one selected by the advertiser. UPX8055 at .001– 02 (April 17, 2012 Google blog post describing initial operation of Exact Match). Google’s next most granular match type is “Phrase Match.” UPX8023 at .002. Similarly, to trigger ads, Phrase Match once required the keyword phrase to be the same as the phrase’s use in the query. UPX8055 at .001–02.

614. In approximately April 2012, Google changed Exact Match and Phrase Match to include “close variants” of the keywords, i.e. misspellings, singular/plural forms, stemmings, accents and abbreviations.” UPX8055 at .002; UPX8100 (Google Ads Help post describing “[n]ew matching behavior for phrase and exact match keywords”).

615. Google initially permitted advertisers to opt campaigns out of the expansions, and advertisers opted out approximately 30% of Exact and Phrase Match revenue. UPX0518 at -573 (within 10 months of expansion, approximately 25% of Exact and Phrase Match revenue had opted out, including top advertisers); Tr. 5478:2–5479:2 (Jerath (Pls. Expert) (ultimately 30% of revenue opted out). Google recognized the value to advertisers of being permitted to opt-out: “If advertisers prefer to have control, . . . they’ll decide to opt-out and they’ll appreciate the option.” UPX0782 at -786 (Nick Fox Mar. 2012 email).

616. However, Google removed the opt-out option in 2014, forcing all match types to accept the expansion to all campaigns. Tr. 1478:12–14 (Dischler (Google)); UPX8049 at .003 (Aug. 14, 2014 Google Blog Post: “For advertisers that opted out, the option to disable close variants will be removed in September [2014]”); Tr. 5478:2–19, 5482:10–17 (Jerath (Pls. Expert)). Google continued to expand its match types, making additional changes in 2017, 2018, and 2019—all, again, without opt-out options. UPX0031 at -471 (showing evolving expansion of keyword match types); UPX8050 at .001–002 (2017 expansion of Close Variants); UPX8040 (2018 expansion of Exact Match to include semantic matches); UPX8099 (2019 expansion of Broad and Phrase Match).

617. Google’s Exact and Phrase Match types have now expanded beyond close variants to include “semantic matching,” which matches keywords to queries containing “analogous words” selected by Google. Tr. 1362:19–1363:16 (Dischler (Google)) (describing implementation of semantic matching in 2018 and 2019).

618. Google has not offered text advertisers a simple, binary “opt out” option from these expanding match types. Tr. 8882:17–21, Tr. 8886:6–21 (Israel (Def. Expert)) (“[Y]ou can opt out of certain keywords but semantic matching is the Google system.”). Google proposes instead that advertisers identify and specify “negative keywords,” which prevent an ad from matching queries containing the negative keyword. Tr. 4298:4–4299:1 (Juda (Google)); Tr. 8882:22–25, 8883:9–15 (Israel (Def. Expert)) (“[I]f there are certain version[s] that would semantically match and they don’t want to be there, they could put in negative keywords.”); UPX8024 at .001 (defining negative keywords).

619. Google, however, provides no close variant or other expansive option for negative keywords, obligating advertisers to first identify as a separate negative keyword each semantic match they might trigger, Tr. 8886:22–8887:13 (Israel (Def. Expert)), and, for each such term, “add synonyms, singular or plural versions, misspellings, and other close variations if [the advertisers] want to exclude them.” UPX8024 at .001–02; UPX0049 at -611 (“[Google’s process] forces advertisers to go through the tedium of continuously adding more and more negatives that are very similar to the ones that they already have.”); UPX0516 at -580–81 (Google summarizing advertiser feedback; “As keywords get more automated, advertisers want more control via usage of negative keywords. . . . Advertisers want . . . the option to choose if they want to expand the negative keyword to misspellings.”). For advertisers with large keyword lists, this can be a tremendous undertaking, if even possible. Tr. 1370:8–11 (Dischler (Google)) (“[W]e have some advertisers who have more than a billion keywords in the system.”).

620. Negative keywords are therefore an inefficient and cumbersome way to opt out of unwanted match-type expansions, particularly when compared to Google’s now-withdrawn optout option. Tr. 5480:18–5481:22, 5513:18–5514:2, 5514:7–5515:18 (Jerath (Pls. Expert)) (Advertisers’ experiences with negative keywords are “inefficient and really cumbersome.”); Tr. 8885:11–8886:2 (Israel (Def. Expert)) (Reviewing UPX0049 at -611 and agreeing that using negative keywords “requires work if there are certain terms that you don’t want;” “this is a challenge of an auction process”). Smaller advertisers face a particularly acute burden. Tr. 5513:18–5515:18 (Jerath (Pls. Expert)) (“[T]he larger advertisers, they may have access to automated resources to generate these things, but the smaller ones won’t.”); Tr. 8886:22– 8887:13 (Israel (Def. Expert)).

621. Moreover, Google has reduced the granularity of information it provides advertisers concerning the queries matching their ads, which exacerbates the already-difficult task of identifying negative keywords. Infra ¶¶ 1172, 1184, 1186.

622. Thicker auctions, i.e. auctions with more participants, generally lead to higher CPCs. Tr. 1478:8–11 (Dischler (Google)); Tr. 3830:23–3831:8 (Lowcock (IPG)) (Increasing the number of bidders in an auction “should increase the price.”); Tr. 8860:5–16 (Israel (Def. Expert)) (“[I]t is probably true on average” that more advertisers in an auction tends to lead to a higher price.); Tr. 5481:23–5482:8, (Jerath (Pls. Expert)) (Thicker auctions “on average” results in “higher prices.”).

623. By expanding match types while removing the ability for advertisers to opt out of the expansions, Google has included advertisers in actions they would have otherwise chosen to avoid, thickening auctions and increasing CPCs. Tr. 5481:23–5482:08, (Jerath (Pls. Expert)) (“THE COURT: And is the concern that by virtue of withdrawing this option, that advertisers will be put into auctions that they otherwise might not want to be a part of and, therefore, creating thicker auctions and the result being a potentially greater price. THE WITNESS: Absolutely . . . this makes it easier for advertisers to enter auctions, but much more difficult for them to not enter these auctions. So on average, that would lead to thicker auctions, exactly as you said, and thicker auctions means more –– higher prices”); Tr. 1477:25–1478:7, (Dischler (Google)).

624. Google acknowledges its keyword expansions increased CPCs. Google determined that its October 2018 Semantic Exact Match expansions increased revenue and that the “Impact on Revenue is due to increased auction pressure, therefore higher CPC: Competitors are now bidding on keywords they weren’t historically competing on so it may cost more to serve on those terms.” UPX0961 at -476; DX0161 at -542 (“This coverage increase also leads to denser auctions and higher CPCs.”).

Google also found that the 2018 expansions pulled advertisers into auctions where they paid 20–30% more than on their pre-expansion Exact Match traffic. Id. at -560 (“New clicks and conversions are, on average, only between 20% and 30% more expensive than existing exact traffic.”); UPX0050 at -072 (for 2019 expansion, advertisers “currently using exact match may see an increase in cost because they are targeting more searches than they were previously.”).

b) Reduced Advertiser Control Over Where Search Ads Appear

625. Google has also reduced advertiser control over where their Search Ads appear. For example, advertisers purchasing shopping ads cannot choose to purchase ads only on the google.com SERP, but must also permit Google, in Google’s discretion, to place their ads on other Google surfaces, i.e., Google’s shopping immersive or images page. UPX8026 at .003 (Google Ads Help explaining that shopping ads can appear on Google Search, Google Images, and Google’s shopping tab); Des. Tr. 32:22–34:22, 48:17–50:13 (James (Amazon) Dep.) (discussing UPX0061 at -437); UPX0061 at -437 (“We [Amazon] want control for where we do and where we do not show our ads. Aligned with Google putting our Shopping Ads on Google Images, and the lack of data, we don’t have the option to be there, or to change our bids for the placement.”).

626. Further, Google does not tell advertisers on which surface(s) Google has chosen to show their ad. Des. Tr. 26:10–18, 36:18–38:9, 160:25–161:14, 161:16–162:9 (James (Amazon) Dep.) (discussing UPX0511 at -619). This impacts the advertiser’s ability to optimize its spend—by, for example, bidding differently for ads on different surfaces. Des. Tr. 32:22– 34:22, 35:9–23, 36:10–17, 48:17–50:13 (James (Amazon) Dep.). (“When Google chooses to take one of our ads and put in on any number of different surfaces, we lack the ability to optimize for that placement.”).

Google’s conduct also requires the advertiser to appear on Google properties the advertiser may prefer to avoid for competitive reasons. Des. Tr. 139:4–140:7 (James (Amazon) Dep.) (Google’s placement of Amazon ads on Google’s shopping immersive “means that Amazon’s brand, as well as products that Amazon makes for sale, are now being leveraged in order to help, you know, another store, effectively, develop and grow their catalog of products.”).

5. Direct Evidence Of Google’s Monopoly Power In The Search Ads And Text Ads Markets

627. Google can, and has, profitably raised advertiser’s prices in the Text Ads market. Infra ¶¶ 629–637 (§ V.C.5.a). This also raises prices in the overall Search Ads markets. Supra ¶ 589 (describing effect on Search Ads markets).

628. This pricing power is one reason Google’s “core business (Search) is incredibly lucrative with unlimited TAM [Total Addressable Market], providing endless capital to allow [it] to hire the best talent and take big risks.” UPX0275 at -078 (“Resources: our). As one Google employee wrote: Search advertising is one of the world’s greatest business models ever created . . . there are certainly illicit businesses (cigarettes or drugs) that could rival these economics, but we are fortunate to have an amazing business. . . . [W]e’ve essentially been able to ignore one of the fundamental laws of economics – businesses need to worry about supply and demand. . . . When talking about revenue, we could mostly ignore the demand side of the equation (users and queries), and only focus on supply side of advertisers, ad formats, and sales. . . . [W]e could essentially tear the economics textbook in half. UPX0038 at -619; Tr. 1694:15–1697:22 (Roszak (Google)) (discussing UPX0038).

a) Google Has Profitably Raised Prices In The Text Ad Market Without Losing Share To Rivals

629. A firm’s ability to profitably raise prices in a relevant market without losing share to rivals is direct evidence of market power. Tr. 4796:12–4797:14, 10473:14–10474:2 (Whinston (Pls. Expert)). Google does this. Tr. 3825:12–24 (Lowcock (IPG)) (“[I]f the price of Google’s text ads increased by 5 percent, would you recommend to your clients to move their ad spend elsewhere? A. No.”); id. 3825:25–3826:10 (IPG clients have not moved spend away from Google despite increases in Google’s Text Ad CPCs).

630. A monopolist selling through an auction it controls possesses multiple levers to influence auction prices. Tr. 465:9–12 (Varian (Google)). Thus, a monopolist auctioneer can exercise its monopoly power to increase prices, including by changing the auction’s design, changing the algorithm than runs the auction, or increasing the auction’s reserve price. Id. 464:1– 465:8.

631. In its Text Ad auctions, Google applies those levers through what it calls “‘intentional’ pricing,” where Google “directly affect[s] pricing through tunings of [its] auction mechanisms, in general through the three levers that are format pricing, squashing, or reserves.” UPX0509 at -869; Tr. 4102:18–4103:2 (Juda (Google)) (Google can directly change how the auction works which impacts pricing).

632. Google has, at times, increased the average advertisers’ CPCs by 5%, Tr. 1208:11–24 (Dischler (Google)), and possibly as much as 10% for some queries. Id. 1209:2– 4; Tr. 8854:3–10 (Israel (Def. Expert)) (not disputing Mr. Dischler’s testimony that Google may raise CPCs 10% on some queries). Although Google’s 5% increase resulted in fewer ads being sold, Tr. 1210:11–24 (Dischler (Google)), it was nevertheless profitable for Google, id. 1209:5– 8.

633. Google admitted increasing CPCs by changing its auction mechanism. Dr. Juda, Google Vice President of Ads, testified that he “would describe it less as raising prices and more coming up with better prices or more fair prices, where those new prices are higher than the previous ones.” Tr. 4110:1–12 (Juda (Google)). Id. 4108:13–15 (“There certainly have been launches where the net aggregate outcome of the launch is that CPCs were higher after the fact rather than before the fact.”); id. 4300:6–25 (Juda describing his participation in launches that increased average CPC); id. 4153:6–10 (discussing UPX0465 at -454) (Juda responsible for 9% annual average “revenue innovation” for each of preceding five years); id. 4157:6–13 (discussing UPX0465 at -454) (“[S]everal billion dollars per year of additional revenue has been generated by pairing Ads UI launches with pricing adjustments (where to my team’s credit the pricing mechanisms have improved since the original launch)”); Tr. 8855:11–20 (Israel (Def. Ex. (Google)) (“I think it’s fair that on average, they’ve [CPCs] gone up”).

634. A firm raising prices to share in (or “extract”) the entire value of its quality improvements is a hallmark of market power. Tr. 10474:6–10475:11 (Whinston (Pls. Expert)). A firm in a competitive market needs to innovate or risk losing business to rivals, providing incentives to innovate. In contrast, for a monopolist to have the ability to innovate, it needs to share in the value created by the innovation. Id. 10477:15-10479:23.

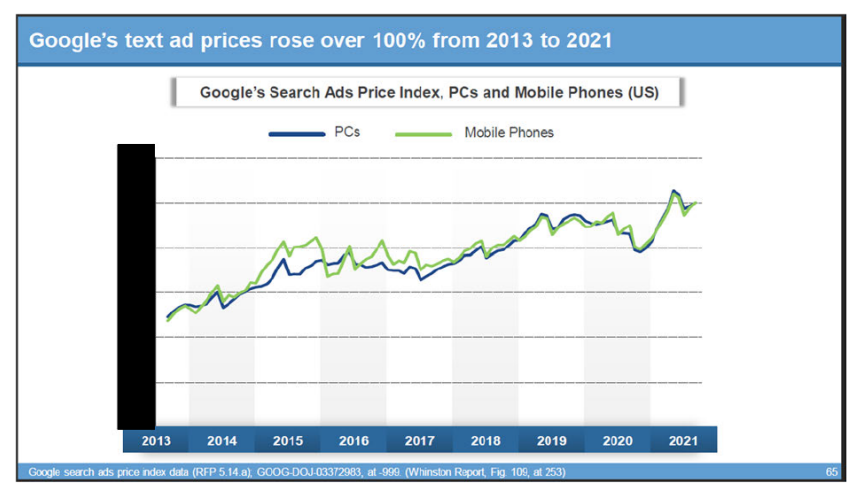

635. Google's own price indexes show its steady price increases. In 2018, Google created a backwards-looking Search Ads Price Index "that accounts for the changing query stream and accurately represents the movement of Search Ads CPCs over time.” UPX0725 at -968. Prof. Whinston's analysis of Google's Search Ads Price Index data shows Text Ads CPCs increased over 100% from 2013 to 2021. Tr. 4782:22-4784:24 (Whinston (Pls. Expert)) (describing UPXD102 at 65).

636. When a monopolist can engage in price discrimination instead of setting a single price for a market, a monopolist need not limit output to exercise market power. Tr.10453:11– 10455:21 (Whinston (Pls. Expert)) (“[I]f you can price discriminate, you can charge different prices to each of the consumers and capture all of that profit, all the surplus from consumers in the limit, if you can price discriminate very well and not even reduce output at all.”).

637. Even absent the ability to price discriminate, in a market where demand is not very responsive, a monopolist need not limit output much or at all to exercise monopoly power and raise prices. Tr. 10453:11–10454:25 (Whinston (Pls. Expert)).

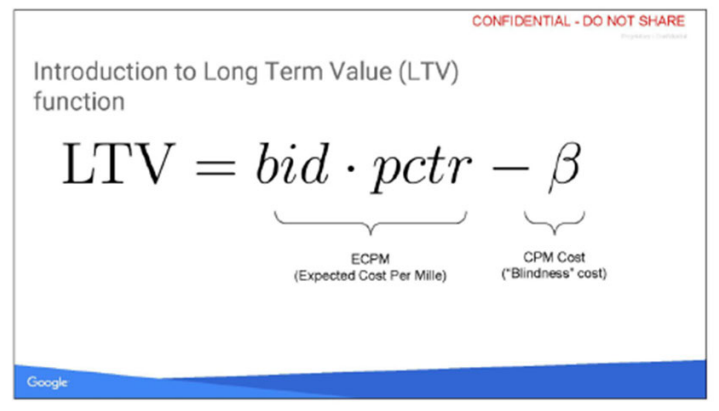

b) Google’s Auction Incorporates Price Modifiers Controlled By Google

638. Google prices Search Ads through a complex ad auction process that ranks and prices ads using an “LTV” formula, which is Google’s estimate of the long-term value of showing the ad in response to a user query. Tr. 4027:16–4028:5, 4033:4–6 (Juda (Google)). Externally, Google refers to LTV as “Ad Rank.” Id. 4030:16–18. Google calculates LTV for every ad that enters a Search Ads auction. Id. 4027:16–4028:5; Tr. 5484:14–5485:1 (Jerath (Pls. Expert)).

639. Google uses LTV as the central ranking variable in its auctions and, if an ad appears and is clicked, Google charges a CPC derived in part from the runner up’s LTV. Tr. 4262:5–18 (Juda (Google)); id. 4017:5–4018:5 (discussing UPX0842 at . 001). If there is no runner up, Google assumes the runner-up’s LTV was zero. Id. 4042:12–16.

640. In the LTV calculation, the advertisers’ bid, multiplied by the predicted clickthrough rate, is Google’s expected revenue, from which it subtracts its expected cost (i.e., Beta/Blindness) to arrive at anticipated LTV. Google incorporates these components into the following formula: UPX0008 at -054; Tr. 4037:2–9 (Juda (Google)).

641. To calculate the LTV of a particular ad, Google’s algorithms produce three predictions, which Google describes as the “quality” components of LTV. Tr. 4248:12–4249:4 (Juda (Google)); UPX0010 at -055:

(a) Its predicted click-through rate, or “pCTR,” which predicts what percentage of viewers will click on the ad if shown in the auctioned position. pCTR has a value between 0 and 1 (i.e., 0–100%). Tr. 4038:8–4039:11 (Juda (Google)) (discussing UPX0008 at -054); UPX0010 at -055.

(b) The ad’s predicted landing page quality, or “pLQ,” which is meant to capture the value of the landing page to which the ad links. pLQ captures “click cost,” which is the effect of clicking on the ad on the user’s willingness to click on ads in the future. Tr. 4096:14–23 (Juda (Google)) (discussing UPX0010 at -055–56) (agreeing pCQ and pLQ variables embedded in LTV equation); Tr. 4014:25– 4015:4 (Juda (Google)) (defining pCQ and pLQ); UPX0010 at -055 (defining “click cost” and “impression cost.”).

(c) Its “predicted creative quality, or “pCQ,” which is Google’s prediction of the quality of the ad’s copy regardless of the landing page. pCQ captures “impression cost” which is how the ad will affect the users’ willingness to click on ads in the future. Tr. 4096:14–23 (Juda (Google)) (discussing UPX0010 at -055–56) (agreeing pCQ and pLQ variables embedded in LTV equation); Tr. 4014:25–4015:4 (Juda (Google)) (defining pCQ and pLQ); UPX0010 at -055 (defining “click cost” and “impression cost.”).

642. In the actual LTV formula, Google combines the pLQ and pCQ components into a single variable, called “β,” or “beta.” UPX0008 at -059. Beta (or “blindness”) predicts the impact of the ad on the viewer’s likelihood of searching and clicking on Google ads in the future. Tr. 4039:20–4040:6 (Juda (Google)); UPX0037 at -200 (illustrating blindness). All else equal, Google higher quality ads get lower beta scores. Tr. 4040:14–24 (Juda (Google)). In contrast, Google associates higher pCTRs with higher quality ads. UPX0010 at -059 (the more users that click on an ad, the more Google learns the “high-quality nature” of the ad).

643. The ad’s bid and pCTR are directly correlated to LTV: an increase in either the bid or pCTR increases LTV. UPX0010 at -055–56. Thus, advertisers with lower bids but higher pCTRs should be able to win auctions with a lower bid and pay a lower price for their slot, absent some modification to the pCTR metric. Tr. 9205:14–9206:25 (Holden (Google)) (“[P]artners that enjoy that higher click-through rate have higher predicted click-through rates in the future and they can bid less to show up in the same location.”).

Similarly, if an ad’s actual click-through rate improves over time, its pCTR will improve, and its CPCs may decline—a phenomena that, as Google recognizes, benefits both advertisers and users. Id. 9205:14–9206:25 (Designing an auction that rewards higher pCTR benefits consumers and improves ads by allowing advertisers “to bid less because users find those ads valuable.”).

644. In contrast, beta is inversely proportional to LTV: if an ad is very low quality, Google assigns it a high beta score, lowering LTV. Tr. 4040:14–4041:3 (Juda (Google)). If an ad is high quality, Google assigns it a low beta score, increasing LTV. Id

645. A higher LTV increases the chances that an ad will appear. Tr. 4239:6–17 (Juda (Google)) (“[W]hen an ad’s LTV score increases, either an ad usually stays in the same position that it had been but will be able to pay a lower cost, all else equal, or the ad rank may increase by sufficiently large amounts that the ad may move higher on the page and, thus, get a higher ad position.”).

Ads with high pCTR, pLQ, and pCQ quality metrics can win an ad auction with a lower bid price. UPX0010 at -056 (“Ads with low quality metrics (i.e., low pCTR, pCQ, and/or pLQ) would need higher bids to successfully compete against ads with higher quality metrics.

And vice versa, high-quality ads can have lower bids and still compete successfully in auctions.”). In fact, a “key element of the LTV algorithm is the inverse relationship between the advertiser’s bid and the increased quality needed to yield a similar ranking if the bid were lowered.” UPX0010 at -056.

646. Google’s ability to choose how to calculate the “quality metrics” and how much weight it assigns to them gives Google the ability to change the ranking and prices generated by the auction. Tr. 4102:18–4103:2 (Juda (Google)) (agreeing that Google “can directly change how the auction works which impacts pricing” and explaining that placing a greater emphasis on quality could change the prices for some ads, which “could cause the overall average prices to go up or down”); Tr. 4113:16–18 Juda (Google)) (agreeing that “the LTV formula can be tuned”).

c) Google Adjusts Its Auction To Extract Advertiser Value And Increase Bid Prices

647. Google sells Text Ads and other Search Ads through a second price auction so that advertisers will not reduce bids to optimize their spend. Tr. 4263:12–4264:11 (Juda (Google)) (Second pricing obviates “need for [advertisers] to worry about small changes in bids to somehow get a better outcome.”).

648. Google inserted “pricing mechanisms with pricing knobs” into its auction to “extract value more directly.” UPX0889 at -783; Tr. 4121:17–4124:22 (Juda (Google)) (discussing UPX0889 at -779, -783).

649. Google expresses particular concern about “runaway winners,” which are auction winners whose LTVs exceed the runner-up’s by a large margin (i.e., 20% or more). UPX0506 at .004 (“Our Belief, or the Pricing Problem. Auction often fails to set price near value, especially in Top-1 (runaway winners).”); Tr. 1221:20–24 (Dischler (Google)) (Google implemented squashing technique in part “to try to prevent runaway winners.”). Runaway winners often appear first on the page and are likely to pay less than their bid due to their relatively high LTV.

650. Google believes a “good CPC is one that is close to (but lower than) the value an advertiser derives from the click,” and therefore seeks to narrow the delta, or “headroom,” between an advertisers’ bid and their CPC. UPX0506 at .004. Google creates pricing knobs through “mechanism development,” described as “improv[ing] the auction score and algorithm . . . by adding new parameters or methods to determine allocation/ranking/pricing. UPX0042 at -106. Mechanism development generates “several billions of dollars in incremental revenue annually.” UPX0042 at -106.

651. Google can use those knobs for “tuning,” which Google defines as adjusting the auction to increase Google’s long-term revenue. UPX0042 at -106; Tr. 1207:4–19 (Dischler (Google)) (Pricing knobs are “an informal way of talking about a parameter tuning within the ad auction function” that allows Google to impact Search Ad pricing); UPX0043 at -582 (“What are we tuning again? Prices! . . . Tuning is just adjusting ranking / pricing.”).

d) Google’s Uses Pricing Knobs To Increase Prices

652. As discussed above, Google’s auction modifies an advertisers’ bid using three quality variables: pCTR, pLQ, and pCQ. Tr. 4144:3–6 (Juda (Google)). Supra ¶ 641.

653. In recent years, Google relied largely on three pricing knobs to adjust prices: format pricing, squashing, and rGSP. UPX0509 at -869 (Google affects pricing through format pricing and squashing); UPX0059 at -620 (rGSP a better knob than format pricing). These knobs insert variables into the auction that can be tuned to affect price. Id. These knobs are not the only means by which Google has tuned its auction to inflate prices. UPX0505 at -308 (as of 2016, “the components of beta are routinely tuned, often independently, in order to improve aggregate Rasta metrics and extract surplus from advertisers.”)

i. Google Used Format Pricing To Increase Prices And Revenue

654. Advertisers can annotate Text Ads with optional pieces of information known as “formats,” or “extensions.” Tr. 4254:3–5, 4254:19–4255:1 (Juda (Google)). In 2012, Google modified its auction to insert a knob permitting it to increase CPCs for ads with formats. UPX0505 at -307–08 (“We launched LIPI in August 2012, an interim solution that charged a constant cost for each format based on height.”); Tr. 1273:10–12 (Dischler (Google)) (Format pricing is “one of the pricing knobs that Google has to adjust the search ads auction.”). In 2014, Google refined its format pricing to price “on the basis of advertiser value from a format.” UPX0042 at -109.

655. Although formats may make an ad more likely to be clicked, Google’s “data indicates that standard formats do not meaningfully change the conversion rate” on a per-click basis. UPX0505 at -315. Google accordingly rationalized its format charges by increased predicted clicks, not increased conversions. Id. (proposing basing format prices on increases in pCTR).

Instead of applying a fixed and transparent format surcharge, Google modified its auction to lower the LTV score of ads with formats, increasing their CPCs. UPX0042 at -109 (“The format normalizer N lowers the LTV score, and therefore increases the cost of the ad.”). The additional charge varied by advertiser and auction, and Google tuned format pricing to modify the degree of inflation. Id.

656. Advertisers could avoid format pricing by choosing not to use formats in their ads. Tr. 4302:1–4 (Juda (Google)). Google sunset format pricing in 2019, after developing a more powerful tuning knob. Id. 4301:15–4302:13 (discussing UPX0059 at -620); UPX0457 at -257 (describing Polyjuice launch in 2019).

657. Upon its retirement, Google replaced format pricing with a new knob called rGSP applying to all ads and all advertisers. UPX0512 at 001–02 (rGSP replaced format pricing); Tr. 4302:24–4303:5 (Juda (Google)); 4302:9–4303:5 (Juda (Google)) (advertisers cannot opt out of rGSP).

658. By the time it replaced format pricing, Google had tuned its format charges to generate approximately 15% to 20% of Google’s Text Ads revenue. UPX0045 at -838–39 (format pricing “had been strongly tuned by our threshold/metrics team to generate ~15% revenue” and was “a very powerful knob which was creating 15% revenue”); UPX0512 at .002 (Format pricing “was at ~20% RPM” when replaced.); UPX0430 at -580 (“Format Pricing contributes materially to Google’s overall profit – adding multiple billion dollars of incremental revenue annually.”).

ii. Google Used Squashing To Increase Bid Prices And Revenue

659. In 2014, Google launched a “squashing” mechanism into its auction through a launch called “Butternut.” UPX0442 at -868. Butternut reduced the delta between pCTR scores among bidders by artificially increasing the pCTR scores of all but the highest-pCTR participant. Id. at -869 (Butternut “pulled up” lower pCTRs “closer to the advertiser with the highest pCTR”). Butternut’s pricing knob controlled the degree of inflation. Id. (“Butternut is introducing a new tuning knob lambda.”); Tr. 4790:19–4791:20 (Whinston (Pls. Expert)) (Squashing boosts the ranking of the bidder who had the second highest pCTR.).

660. Squashing increased CPCs by reducing the impact of the pCTR quality metric on LTV and increasing the impact of the advertisers’ bid. UPX0430 at -581 (Squashing “compresses the pCTRs and puts more weight on bid in the pricing/ranking function.”);

661. Because of this reduced emphasis on quality and increased emphasis on bid, Google recognized squashing “[r]anks ads sub-optimally in exchange for more revenue.” UPX0051 at -241; PSX00167 at -212 ("Squashing down-weighs the importance of pCTR in ranking and can have negative user experience consequences, as well as a negative impact on the long-term incentives for advertisers to improve quality.”).

662. In fact, four years before Google launched squashing, Dr. Varian cited squashing's detrimental effect on quality as a reason why “we [Google] don't do ‘squashing' and never have. In fact, we have done the opposite of squashing in the AdSense auction, where we overweighted quality a bit, reducing revenue but increasing CTR." UPX0716 at -219 (emphasis removed).

663. Butternut and later squashing launches increased average CPCs. Tr. 1222:6–10 (Dischler (Google)); Tr. 8857:4–13 (Israel (Def. Expert)) (“Everything else the same and you squash, and I agree that 39 cents would go up."); UPX0520 at -821 ("We will keep the pCTR squashing of Butternut to leverage second pricing to set higher prices for pCTR winners.”).

664. Although Google claims it implemented squashing to (in part) capture revenue losses caused by other innovations, the company acknowledges that squashing increases CPCs indiscriminately. UPX0442 at -869 (“One issue with pCTR squashing is that, while it does correct for the revenue loss from a SmartASS launch at an aggregate level, the revenue increase664. it engenders is not limited to the ads which saw a pricing decrease due to the SmartASS launch.").

665. Google also claimed it implemented squashing to allow “folks other than the predominant winner to break through some percentage of the time,” Tr. 1386:10–1387:3 (Dischler (Google)). Google’s own analysis, however, shows that “[s]quashing [didn’t] change the ads we show very much,” showing the same ads on about 95% of queries measured by impressions and clicks, and generating 88% of its revenue from queries where it returned the same top ads. UPX0442 at -872.

Moreover, Google’s internal documents show it viewed reranking advertisements as an undesirable outcome and as the “collateral damage” of squashing, not a benefit. UPX0737 at -464 (“Squashing in itself can lead to both desirable (CPC increase) or undesirable outcomes (CPC decrease, reranking) . . .”); UPX0430 at -589 (“The Squashing mechanism has high collateral damage (clicks lost due to re-ranking, and CPC decreases due to squashing against a winning ad with lower pCTR than the runner-up).”).

iii. Google Uses rGSP To Increase Prices

666. In 2019, Google launched a new knob called rGSP, or “randomized generalized second price,” which introduced a “randomization” mechanism into the auction. UPX0457 at -257–58; Tr. 4175:13–16 (Juda (Google)); Tr. 1222:11–22 (Dischler (Google)). Google named its rGSP launch “Polyjuice,” which in the Harry Potter stories is a potion allowing someone to disguise themselves as someone else. Tr. 4180:21–4181:10 (Juda (Google)).

667. For Google, rGSP was “[a] better pricing knob than format pricing,” DX0153 at -102, because, among other things, it had the “the ability to raise prices (shift the curve upwards or make it steeper at the higher end) in small increments over time (AKA ‘inflation’).” UPX0059 at -620. rGSP also applied in all auctions and to all advertisers, solving Google’s concerns that other knobs did not apply universally. Tr. 4301:15–4303:5 (Juda (Google)) (advertisers cannot opt out of rGSP); PSX00211 at -139 (“One negative with our existing launched knobs of format

pricing and squashing is that they can only extract revenue on advertisers with large format combinations or queries with competition.").

668. rGSP modified the auction so that merely winning was not enough advertisers "have to beat the other person substantially to win for sure” and pay a higher CPC when they win. UPX0512 at .015.

669. Under rGSP, Google first runs the auction as before: calculating LTV, ranking eligible ads, and identifying the winner and runner-up. UPX1045 at -422 (rGSP starts with "top 2 LTV ads in given auction"); Tr. 5491:12-22 Jerath (Pls. Expert)) (discussing UPXD103 at 43)).

However, rGSP then inflates the runner-up's LTV while leaving the winner's constant, or, if there is no runner up, inflates the reserve price while leaving the winner's constant. Id. The degree of inflation—called “Alpha”—is rGSP's pricing knob, which Google can tune. UPX1045 at -422 (Among the "rGSP Parameters" Alpha is the "pricing" knob," and rGSP multiplies the runner-up's LTV by Alpha to determine whether to swap the winner with the runner-up based on a specific probability another rGSP parameter.).

670. After inflating the runner up's LTV, Google then checks to see if the original winner's LTV exceeds even the inflated runner up LTV. Tr. 5492:8–22 (Jerath (Pls. Expert)) (discussing UPXD103 at 43); UPX1045 at -422. If so, the original winner gets the slot, but Google now computes the CPC using the runner up's inflated ad rank instead of its original ad rank. Id. That is, under this scenario, the rGSP pricing knob operates to increase the auction winner's price by inflating the runner-up LTV against which the winner's CPC is computed. Id.

671. In the other scenario where the runner-up's inflated LTV exceeds the winner's Google randomly selects between the two ads (or, in the case of a reserve priced ad, randomly selects whether the winner will or will not appear). Tr. 5492:8–22 (Jerath (Pls. Expert)) (discussing UPXD103 at 43); UPX1045 at -422.

672. Importantly, in either scenario, if the original winner’s ad displays and is clicked, that winner will pay a higher CPC than they would have absent the rGSP mechanism:

[C]onsider the situation where the positions are not flipped, they’re not swapped. Even in that case, the winning ad’s price increases. The reason is that the ad rank of the original runner-up, which is a runner-up here, so the ad rank of the runnerup is inflated. And this is a second-price auction so the price of the winner is determined by the ad rank of the runner-up. And if the runner-up’s ad rank is artificially inflated, then the winner’s price goes up sort of artificially.

Tr. 5492:8–22 (Jerath (Pls. Expert)).

673. Under the randomization option, the original winner’s odds of being again selected as the winner are proportional to the size of the delta between the two ads’ original LTV scores, and an advertiser can avoid the threat of being swapped entirely by raising its bid. Tr. 4176:21–4177:25 (Juda (Google)) (discussing UPX1045 at -393). rGSP thus incentivizes higher bidding. Tr. 5492:23–5493:16 (Jerath (Pls. Expert)); Tr. 8877:15–8878:1 (Israel (Def. Expert)) (rGSP incentivizes higher bids); Tr. 4188:22–4190:3 (Juda (Google)) (discussing UPX0059 at -620) (“If I have to say ‘we randomly disable you if you don’t bid high enough,’ I’m going to have another bad year at GMN [Google Marketing Next].”).

674. As of early 2020, an advertiser needed to have an ad rank [redacted] that of the runner-up’s to avoid the risk of swapping and, in reserve-priced auctions, needed to have an ad rank [redacted] that of the runner up’s to avoid the risk of being dropped. UPX0466 at -939 (The “tuning point” for rGSP Alpha was [redacted] for US Mobile in second priced auctions, and [redacted] in reserve priced auctions); Tr. 4178:8–14 (Juda (Google)) (It was “possible” the auction winner would have to bid 3.7 times higher than the runner-up to avoid swapping.).

675. rGSP increased Google’s revenue. Tr. 1224:23–24 (Dischler (Google)). Google’s pre-launch experiments indicated that rGSP would increase CPCs for top slot ads on nonnavigational queries 5.91% on PCs and tablets and 4.85% on mobile phones. UPX0457 at -260 (“TopNonNavCPC” column). Experiments showed a 5.74% revenue gain persisted two months after launch. UPX0045 at -838. Given that rGSP replaced the 15% format pricing knob, this meant rGSP “replaced 15% revenue and got x% on top of that.” Id.

676. As with squashing, Google describes the reranking scenario—i.e., where the runner-up is awarded the slot due to random reranking—as the “loss case” and the scenario where the original winner keeps the slot but pays a higher CPC as the “gain case.” UPX0512 at .016.

e) Google’s Use Of Pricing Knobs To Extract Advertiser Value Constitutes Direct Evidence Of Monopoly Power

677. It is not merely the presence of pricing knobs that evince Google’s monopoly power, but rather Google’s use of those knobs to exercise that power. Google bases its Text Ad pricing almost entirely on extracting what it called “advertiser value” from advertisers, seeking to adjust its second price auction to set advertiser prices “one penny less than the breaking point.” UPX0036 at -067. Google pays little or no attention to the quality and pricing of its claimed rivals. Infra ¶¶ 725–727 (§ V.C.6). These are all hallmarks of substantial market power.

678. Since 2012 on desktop and 2015 on mobile, increased RPM, rather than overall query growth, has driven Google’s Search Ads revenue growth and its progress towards its 20% annual objective. Tr. 7550:24–7551:18 (Raghavan (Google)) (referring to redacted figures in UPX0342 at -825 and agreeing that the majority of Search Ads revenue growth comes from RPM); UPX0342 at -826 (“RPM has become the dominant growth driver”)).

679. These RPM increases have been largely driven by Google’s Ad Quality division, including by implementing and tuning the knobs described above. Inside the team working on the auction, as of 2018, there was a “general belief” that “there’s more juice in getting prices right (higher) than in improving the allocation of ads.” UPX0467 at -332. Tr. 4146:4–9 (Juda (Google)).

680. Google introduced format pricing in 2012, UPX0042 at -109, when RPM began outpacing query growth on desktop. Shortly before Google’s RPM growth overtook query growth on mobile in 2015, Google introduced its first squashing iteration and refined its format pricing to price “on the basis of advertiser value from a format.” UPX0042 at -109. Along with rGSP, these tools enabled Google to implement long-term CPC increases. Tr.1220:5–9 (Dischler (Google)) (Format pricing tuning increased CPC on net.); id. 1222:6–10 (Squashing increases ad prices on average); UPX0059 at -620 (Randomization is “[e]asy to tune, with the ability to raise prices.”).

f) Google’s Internal Modeling And Live Experiments Demonstrate Google’s Ability To Raise Prices At Will

i. Google’s GammaYellow And Kabocha Experiments Show It Can Sustain Price Increases

681. In connection with a series of price-raising initiatives starting around 2017, Google conducted multiple experiments assessing advertiser response to its price increases, ultimately concluding advertiser response was low. Tr. 4791:21–4793:1 (Whinston (Pls. Expert). Google’s ultimate takeaway was that if it raised CPCs, it could expect to realize approximately half the increase in its revenue (i.e., if it increased CPCs by 10%, Text Ad revenue would go up 5%). Id. Google, accordingly, launched multiple price increases using all three of its tuning knobs.

682. One such experiment was GammaYellow, which Google designed to assess its ability to sustain long-term price increases for ad formats. UPX0729 at -979 (“[T]he goal of the GammaYellow [Advertiser Experiment] was to evaluate the long-term revenue effects of raised format prices.”) (emphasis omitted). GammaYellow “exposed 15% of advertisers to strongly increased format prices on non-nav google.com traffic for 6 weeks in Q2’17.” UPX0729 at -979; UPX0036 at -064 (“GY [GammaYellow] was 20% on mobile on average.”); Tr. 4791:21–4793:1 (Whinston (Pls. Expert)) (outlining experiments).

In GammaYellow, Google “found that 50% of the initial revenue gains stuck” and “found no evidence of notable format opt-out behavior.” UPX0729 at -979 (emphasis omitted); Tr. 4791:21–4793:1 (Whinston (Pls. Expert)) (“[B]asically there’s what they called a stickage of 50 percent. So if they raised prices 10 percent, revenue would go up 5 [percent].”).

683. Google followed GammaYellow with Kabocha, which assessed Google’s ability to sustain long-term price increases through squashing and which “confirmed that the stickage factor for this knob was also . . . roughly 50%.” UPX0737 at -462; id. at -476 (Similar to format pricing, Kabocha “showed that ~50% of the initial RPM effect [from squashing] sticks in the long term.”); UPX0745 at -085 (Kabocha “validated squashing is long term revenue positive.”).

684. Between these experiments—in mid-2017—Google conducted a “Macro ROI” investigation, which conducted a series of advertiser interviews aimed at assessing if “format price increases on google.com [would] influence long-term spend allocation to Google.” Tr. 1276:19–24 (Dischler (Google)) (explaining UPX0519 at .001). Google concluded that “a 15% percent CPC should be ok when it comes down to the long-term budget decisions… as long as we are smart about it.” Id. at .003. Being “smart about it” meant “don’t touch brand [name keywords], check for outliers, and consider gradual price increases (rather than a sudden step function).” Id. at .001.

685. Google reached this conclusion because the “overwhelming majority” of advertisers could not measure actual ROI, i.e., incremental sales gained from advertising, instead optimizing for other factors used as a proxy for ROI. UPX0519 at .001, .009; id. at .005 (defining “true ROI” as incremental revenue per dollar of ad spend). Thus, Google concluded that, when raising prices, it “should be more concerned about the perception of price/ROI changing within a channel rather than actual cross channel ROI comparisons.” UPX0519 at .001 (emphasis omitted).

ii. Momiji: Google Exercises Monopoly Power By Capturing Advertiser Value And Higher Prices

686. Following its Macro ROI analysis, Google launched “Momiji.” Momiji was a Google project through which the company sought to “better understand the impact of raising prices on our ecosystem and to make significant changes to the prices in our system if the data warranted such action.” UPX0456 at -274; Tr. 4786:7–4787:9, 4788:6–4790:17 (Whinston (Pls. Expert)) (discussing UPX0036 at -063, -067; “Momiji was trying to figure out, you know, can we raise prices, how much can we raise prices, how should we raise prices.”).

687. Momiji relied on format pricing to effectuate higher prices. UPX0456 at -274 (“Thresholds has developed two mechanisms which can effectively set better prices (Squashing and Format Pricing) . . . We chose to vet Format Pricing first because we believe it to be our best pricing knob currently available for use.”); UPX0506 at -005 (“Purpose of Momiji Format Pricing . . . Increasing Top-1 CPCs to better reflect value.”).

688. In Momiji, Google read GammaYellow and related experiments to mean that Google need not accept auctions with a so-called “runaway winner,” i.e., where the winner’s ad rank was meaningfully higher than the runner-up’s. Google thus sought to capture this delta (which it called “headroom”) under the philosophy that, for pricing, “one penny less than the breaking point is the right amount.” Supra ¶ 650; Tr. 4788:5–4790:17, 4789:15–4790:9 (Whinston (Pls. Expert)) (discussing UPX0036 at -067); UPX0507 at .004 (“~50 of Top-1 second price spend has > 20% LTV gap with runner up . . . GammaYellow: Prices could be higher, and we think we would keep the money . . . Revenue gain from higher prices > revenue loss from response.”)

689. Google eventually launched Momiji by increasing prices for formats, which “was only able to proceed after the GammaYellow advertiser experiment validated that expensive formats was long term revenue positive.” UPX0456 at -273. This took place in 2017. UPX0042 at -110 (“July 2017: Project Momiji effort to tune AlphaRed for lots of long-term revenue.”). Momiji increased prices for the typical advertiser. Tr. 1274:16–1275:3 (Dischler (Google)).

690. Google raised prices on formats in Momiji because it felt format pricing was its “best knob to engender large price increases.” UPX0507 at .026. Google’s Momiji launch review states explicitly that it did not have a principled basis for choosing the amount of the increase: “Most gains are in Top-1 [ad position], where we have no way to say what formats should cost.” UPX0507 at .026.

iii. Google Used Holistic Pricing To Increase Prices

691. Google’s “Holistic Pricing” effort sought to identify areas where prices were “unusually low” relative to where Google believed prices should be. Tr. 4127:8–12 (Juda (Google)). Through Holistic Pricing, Google sought to “develop a holistic plan for a series of pricing increases using existing knobs (Format Pricing, Squashing) and new mechanisms on Google.com and AFS.” UPX0042 at -117. The initiative ultimately led to a series of pricing launches that “increas[ed Google’s] revenue by billions with more appropriate prices.” UPX0454 at -642; Tr. 6155:25–6158:7 (Whinston (Pls. Expert)) (Google’s “goal” in Holistic Pricing was “to make sure that whatever improvements there were for advertisers, Google got all of it.”).

692. Google’s Holistic Pricing initiative began in early 2018 and ended in late 2019. UPX6015 at -314, -320–21. It proposed a series of “lenses” or “tools” to assess Google’s long-term power to maintain price increases: UPX1054 at -052–54.

693. One Holistic Pricing tool/lens was “Long Term Response Measurement,” including experiments intended to assess the “stickage” of price increases. UPX1054 at -052.

694. Second, Google contemplated quarterly Holistic Pricing tunings, which would, each quarter, tune the auction to increase CPCs and extract any “value-price mismatch” Google assessed it had created in the prior quarter. Id. at -054, -074.

695. A third involved an ongoing “ROI Perception” study, where Google’s CX Lab division would conduct a series of interviews with a cohort of advertisers before and during the quarterly tunings to assess if the price increases affected the advertisers’ “perception” of Google search ROI. Id. at -053.

696. Finally, Google sought to create a Search Ads price index that would enable it to track CPCs over time. Id.; supra ¶ 635. This tracking would allow Google to assess if it could increase price.

697. Google first assessed long-term advertiser reaction to price hikes with “AION,” a March 2018 experiment which—similar to GammaYellow—increased format pricing on a cohort of advertisers, but which lasted for [redacted]. UPX0745 at -085; UPX0737 at -462. After three months, AION’s results mirrored GammaYellow’s: “Spend response trends to the 15% change have stabilized at roughly half the initial gains.” UPX0737 at -462; Tr. 4791:21–4793:1 (Whinston (Pls. Expert)) (three-month pricing experiment showed limited advertiser response to price increase). AION concluded after [redacted], showing Google’s format price increases persisted throughout its [redacted] run. UPX0509 at -958 (AION showed “that [redacted] spend stickage to a detectable price increase matched shorter 6 week responses.”).

698. Google implemented six “Holistic Pricing Quarterly Tunings” between July 2018 and November 2019. UPX6015 at -314, -321–23 (describing Potiron (July 2018), SugarMaple (Sept. 2018), Q4 2018 HP Tuning, Q1 2019 HP Tuning, July 2019 Excess CPC Tuning, and Polyjuice (Nov. 2019)). Google’s CX Lab contemporaneously performed four rounds of ROI Perception interviews, including three between February and July 2018, and a follow-up round with a different cohort of advertisers in August 2019. DX0187 at -614, -691; DX0119 at -388.

The interviews’ stated purpose was to “inform[] holistic pricing effort on how we should think about long term response implications.” DX0187 at -691. The 2018 interviews “raised no red flags” related to the ongoing Holistic Pricing work, and the 2019 interviews remained largely consistent with the 2018 work. DX0187 at -693, -622–25.

699. Google’s ROI Perception interviews assured Google that its price increases did not lead to advertisers’ shifting away from Google; advertisers viewed “things in the world or what they’ve done, not something happening on the back end” at Google as responsible for the price increases. UPX0737 at -464; UPX1054 at -060–61 (Advertisers faced with CPC changes “dominantly attribute these shifts to themselves, competition and seasonality (85%+)- not Google.”).

700. Through the Holistic Pricing Quarterly Tunings, Google sought to ensure that advertisers would not benefit from any changes to Google’s advertising products that increased the click-through rate on its Text Ads. Tr. 10475:9–10476:21 (Whinston (Pls. Expert)) (“So what Google sought out to do was to say, no . . . we’re increasing clicks, we’re going to make -- we’re going to raise prices to make sure advertisers are not gaining from that, like, we’re going to be the ones who gain from it”) (discussing UPXD106 at -007–08).

701. Google seeks to price its Text Ads so that each additional click an advertiser receives costs more in CPC than the previous one. Tr. 6032:8–6033:19 (Whinston (Pls. Expert)) (“[I]f I get more bananas at the store, I pay more in total, but my price per banana hasn’t gone up. In these auctions, it’s as if my price per banana does go up”); Tr. 6032:25–6033:3 (Whinston (Pls. Expert)) (describing click cost curve). But Google has no reason to believe the additional, more expensive clicks are more likely to convert than earlier clicks. Tr. 6034:1–6 (Whinston (Pls. Expert)) (“Q. This is a more valuable banana, right? A. You know, it’s not clear.”) (analogizing bananas to ad formats).

In fact, Google recognizes the opposite: its concept of advertiser value means that “ROI should decline with [click] volume.” UPX0430 at -589; UPX0520 at -816 (“ROI should decrease monotonically with click volume (i.e. marginal CPC should increase monotonically with volume).”).

702. Google’s Holistic Pricing Quarterly Tunings sought to ensure advertisers’ CPCs would increase at the same rate both before and after a launch, such that Google would extract the entire benefit of a value-generating launch. 6155:25–6158:9, 6158:18–6159:2 (Whinston (Pls. Expert)). Google did this using a newly-created metric called Excess CPC or Negative Excess CPC. 6155:25–6158:9, 6158:18–6159:2 (Whinston (Pls. Expert)) (Holistic Pricing used Excess CPC to ensure “that whatever improvements there were for advertisers, Google got all of it.”).

703. For example, Google’s first Holistic Pricing Quarterly Tuning—“Potiron”— sought to increase CPCs Google believed were “underpriced,” but noted that “by underpriced we mean that the cost of incremental clicks did not rise along with volume following the original click cost curve.” UPX0737 at -462. Google accordingly used the squashing knob to increase CPCs for those incremental clicks. Id. at -461 (Potiron adjusted auction to capture Excess CPC).

704. Google’s second Holistic Pricing Quarterly Tuning—“SugarMaple”—similarly tuned the auction to ensure “that in aggregate 100 clicks stay $X while making sure the incremental cost of clicks increases in a consistent fashion,” this time using the format pricing knob. UPX0039 at .002. Put differently, SugarMaple was “all about keeping the current tradeoffs stable.” Id. The experiment results for SugarMaple predicted a 3% increase in CPCs for top ads, a minor drop in the click through rate for top ads, and no other changes related to the launch. Des. Tr. 178:20–179:6 (Miller (Google) Dep.) (discussing UPX0521 at -901).

705. Holistic Pricing raised aggregate CPC prices. Tr. 4127:24–4128:23 (Juda (Google)) (acknowledging prior statement that the sum of the “aggregate change in aggregate CPCs” was possibly positive); UPX0042 at -107 (“[O]ur belief, based on analyses of the system and from advertiser experiments, is that there is a lot of opportunity to increase prices for search ads. . . We call this work value based pricing.”).

g) Google Exercised Pricing Power To Meet Revenue Goals

706. Google has used pricing knobs and other mechanisms to raise price when necessary to meet its quarterly goals. Tr. 1215:10–1216:23 (Dischler (Google)) (“shaking the cushions” to generate revenue and meet quarterly forecasts, with reference to email in UPX0522 at -193).

707. One example was the “Code Yellow” called on February 5, 2019, by Mr. Dischler across Chrome, Search, and Ads because Google’s revenue was weaker than expected. UPX0738 at -406; Des. Tr. 205:10–15 (Miller (Google) Dep.). At Google, a Code Yellow occurs when an issue arises that requires extra engineering or sales efforts to address. Des. Tr. 66:18–22 (Miller (Google) Dep.).

708. Mr. Dischler's Code Yellow notice (1) explained that the timing of "revenue launches" was behind the prior year and (2) formulated a workstream whose "top priority" was to “deliver Q1 revenue launches during February.” UPX0738 at -406.

709. Shortly thereafter, Google Vice President of Ads Finance Andy Miller sent a status update identifying three ad launches to close the revenue gap, including two auction changes “around pricing and ad load." Des. Tr. 207:16-23, 208:3-22 (Miller (Google) Dep.) (discussing UPX0514 at -386).

710. By March 22, 2019, google had met the criteria to exit the Code Yellow, due in part to a format pricing launch known as SugarShack. UPX0733 AT -203 (Code Yellow ends “with the launch of ‘Sugarshack“). With SugarShack, Google’s Search Ads team das “launched all projects necessary to push the team over the quarterly estimated 5% long term incremental RPM target,“ thereby fulfilling the Code Yellow goals, UPX0733 at -203-04; Des. Tr. 209:22-210:2 (Miller (Google) Dep.) (identifying UPX0733at -203-04 as the e-mail announcing that the ads team had met the exit criteria for the code yellow); Des. Tr. 211:2-21 (Google) Dep.) (SugarShack assisted with end of Code Yellow).

b) Google’s Ads Quality Division Has Met An Annual Goal Of 20% Revenue Increases In Search Ads

711. Google expected its Search Ads team to implement launches generating at least 20% in “revenue innovation” annually. Tr. 4153:6–4154:4 (Juda (Google)). Google formalizes this 20% requirement in an OKR (Objectives and Key Results). Tr. 7547:6–14 (Raghavan (Google)) (Search Ads team has an OKR seeking 20% revenue growth for Search).

712. Largely because of efforts by its Ads Quality team, the Search Ads team has consistently met its 20% goal. Tr. 4140:25-4141:3 (Juda (Google)); id. 4130:15-4131:12 (explaining UPX0467 at -331 and agreeing that the "overwhelming majority" of the Search Ads 20% RPM OKR has been driven by the Ads Quality Team); Tr. 7549:6–9 (Raghavan (Google)) (reviewing UPX0342 at -824).

i) Google’s Lack Of Pricing Transparency

713. Google’s ability to maintain a lack of transparency into its pricing mechanisms, against the will of and to the detriment of advertisers, is further evidence of its monopoly power.

i. Google Does Not Disclose Its Pricing Launches

714. Google does not disclose its pricing launches to advertisers. Tr. 1226:13–17 (Dischler (Google)) (“We tend not to tell advertisers about pricing changes.”). This impedes advertisers’ ability to respond and optimize their bidding strategies.

ii. Google’s Own Employees Could Not Understand Its rGSP Disclosure

715. Google claims it publicly disclosed rGSP by editing an online help page to contain the following language:

The competitiveness of an auction - If two ads competing for the same position have similar ad ranks, each will have a similar opportunity to win that position. As the gap in ad rank between two advertisers’ ads grows, the higher-ranking ad will be more likely to win but also may pay a higher cost per click for the benefit of the increased certainty of winning.

UPX6058 at -003; Tr. 4278:14–4279:7 (Juda (Google)) (describing UPX6058, stating that “[t]his appears to be a description of the rGSP launch”).

716. However, Mr. Miller, when presented with his own email containing the purportedly disclosing language and other internal information, could not explain how rGSP functioned, acknowledged the language was “confusing,” and when directly asked if “there was a randomization component introduced into the auction in connection” with the launch, responded “I don’t know if it was a randomization. I don’t know the mechanism that we used to try to do this.” Des. Tr. 192:13–24, 193:5–194:16 (Miller (Google) Dep.) (discussing UPX2020 at -938).

717. Google specifically refrained from broadcasting a disclosure of rGSP to its sales staff. UPX2020 at -938 (“Relevant GTM and finance leads have been notified in region, but we are not broadcasting this change to sales given there is no action required and no change to how advertisers should continue to manage their Google Ads account.”). Des. Tr. 196:5–20 (Miller (Google) Dep.) (discussing UPX2020).

iii. Google Limits Visibility Into Its “Black Box” Auctions

718. Google provides limited visibility into its ad auction and the quality metrics it assigns ads and advertisers. As a result, if an advertiser wants to increase its ad position in the shorter term, the advertiser’s only viable option is to increase its bid. Des. Tr. 221:7–222:8 (Alberts (Dentsu)) (If an advertiser’s quality score is “not a ten out of ten,” it must make sure it bids enough to achieve top placement.); Tr. 5488:2–5489:10 (Jerath (Pls. Expert)) (“[A]s a practical matter, what the advertisers have to work with is the bid, because that has impact in the short term”).

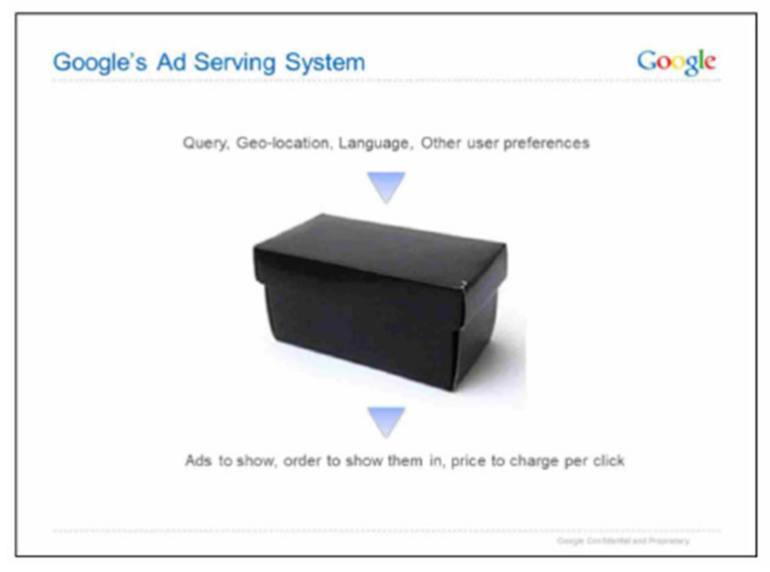

719. Google’s self-controlled auction and ad serving system is opaque to advertisers, who view it as a “black box.” Tr. 3850:12–18 (Lowcock (IPG)) (Google Search is a “black box” because advertisers “have no true visibility into the way that the price is determined or how the auction is conducted.”); id. 3829:16–3830:20 (naming increasing floor prices, advertisers paying for more keywords, and changes to bidding systems as possible reasons--among a “myriad of reasons” for advertising price increases); Des. Tr. 109:10–110:5 (James (Amazon) Dep.) (Google controls the terms its Text Ad and shopping ad auctions); id. 147:19–149:5, 149:17–150:23, 154:17–23 (“[T]he bidding system itself [for Text Ads], the black box, we don’t have concrete knowledge in terms of how it functions. . . [T]his is a proprietary technology that Google owns and so it is a black box. . . I would refer to both [Text Ad and shopping ad] auctions as being black boxes.”); Tr. 5484:14–5487:13 (Jerath (Pls. Expert)) (discussing UPXD103 at 42). Google agrees:

UPX0925 at -765.

720. For example, as described above, LTV is central to Google’s ad mechanism, yet Google does not tell advertisers how Google calculates LTV or what the actual LTV is for any specific ad. Tr. 4293:3–4296:3 (Juda (Google)) (discussing DXD-11 at .009 and explaining that advertisers only know the exact value of the bid); id. 4043:19–4044:7 (Google provides neither the details of its LTV calculations nor the final LTV values to advertisers.); Des. Tr. 216:16– 220:13 (Alberts (Dentsu) Dep.) (Advertisers lack “direct visibility” into Ad Rank quality metrics); Des. Tr. 256:8–257:2 (James (Amazon) Dep.) (Auction history would enable Amazon to better optimize bidding.); Tr. 5484:14–5485:1 (Jerath (Pls. Expert)) (discussing UPXD103 at 42). Advertisers have complained to Google about this. Des. Tr. 257:3–8 (James (Amazon) Dep.).

721. The information Google does provide to advertisers regarding Google’s ad auction is not actionable. Tr. 5485:2–5487:13, 5488:2–5489:10 (Jerath (Pls. Expert)) (discussing UPXD103 at 42). Google provides advertisers a “Quality Score” of 1 through 10 for their ads on a keyword basis, but the score (a) is an aggregation of already heavily aggregated components, and (b) is not actually used in any individual auction. Tr. 5485:2–16 (Jerath (Pls. Expert)) (discussing UPXD103 at 42); Tr. 4013:10–22, 4014:2–7 (Juda (Google)); Des. Tr. 154:24– 155:10 (James (Amazon) Dep.) (Quality Score is only “a loose interpretation of how Google deems the quality of the ad to be.”).

722. An advertiser’s price for its Search Ads is not affected by the Quality Score provided to advertisers, but instead by the more specific quality signals used in the auction itself. Tr. 4020:6–13 (Juda (Google)); UPX0010 at -061–62 & n.34 (describing actual quality metrics used in auction); UPX8025 at .001 (“Quality Score is not a key performance indicator and should not be optimized or aggregated with the rest of your data. Quality Score is not an input in the ad auction.”).

723. Advertisers thus cannot use Quality Score to optimize advertising and bidding. Google acknowledges this, stating “Quality Score is too coarse and can’t be used for finetuning.” UPX0454 at -645; Tr. 5485:2–16 (Jerath (Pls. Expert)) (discussing UPXD103 at 42); Des. Tr. 258:2–258:13 (James (Amazon) Dep.) (“[Q]uality score is a collection of different metrics and therefore it makes it hard for us to understand how we might interpret quality score or use it to our advantage.”).

724. As another example, Google provides advertisers heavily aggregated metrics identifying their predicted click-through rate, ad relevance, and landing page quality as above average, average, or below average. Tr. 5485:17–5487:13 (Jerath (Pls. Expert)) (discussing UPXD103 at 42). The metrics provided to advertisers are based on only the subset of queries matching the advertiser exactly and are aggregated over 90 days; these limits make the metrics impossible to use for short-term response and largely useless. Id.

6. Google Does Not Consider Its Competitors When Pricing Or Making Other Changes To Its Text Ads Auction

725. Google’s analysis into the effects of CPC increases fails to consider the pricing of Google’s rivals. Tr. 4292:14–16 (Juda (Google)) (“not aware of anyone at Google ever doing any analysis of pricing of Search Ads at Bing”). As it acknowledges internally, Google has “never really had market pressure to clean up advertising.” UPX0461 at -732.

726. Although advertisers and other industry participants view Bing as Google’s primary search competitor and seek to split budgets between the two, supra ¶ 588, Google performs no analysis of Bing’s auction model or of the pricing of Search Ads at Bing, nor has Google performed such analysis in the past. Tr. 4292:9–16 (Juda (Google)). Similarly, Google’s Text and Search Ads algorithms lack any variable incorporating the cost of advertising on other digital platforms into Google’s calculation of Search Ad prices. Tr. 4290:20–4291:1 (Juda (Google)) (responding to question from Court).

727. Google’s internal considerations of its ability to continue to meet its annual Search Ads revenue growth targets do not identify competitors or competition as obstacles to that goal. Tr. 4148:8–4149:7 (Juda (Google)) (discussing UPX0467). Google’s extensive process for considering and testing user interface changes related to Text Ads includes no consideration of competition with Facebook. Des. Tr. 202:17–24 (Jain (Google) Dep.). Also, Google did not consider Bing when making decisions about its own ad load. Des. Tr. 79:21–80:10 (Fox (Google) Dep.).

Continue Reading Here.

About HackerNoon Legal PDF Series: We bring you the most important technical and insightful public domain court case filings.

This court case retrieved on April 30, 2024, storage.courtlistener is part of the public domain. The court-created documents are works of the federal government, and under copyright law, are automatically placed in the public domain and may be shared without legal restriction.